Confrontation of prejudice is not always easy, but is essential in breaking down barriers. At 22 years old, Jamal Gerald, a black, gay, performance artist is embarking on his first UK tour with the provocatively named show “FADoubleGOT”.

Using his one man show to tell his own personal story of the highs, lows and in-betweens of growing up as a black gay man, Jamal draws on his experiences to confront the use of prejudicial language and anecdotally tells tales of sex parties, hook-up’s, relationships and Grindr dates; mixed in with candid accounts of surviving periods of self-loathing, experiences of racism and homophobia and of his internalised conflict between his religion and his sexuality. Following opening his tour at Doncaster CAST Theatre, Jamal spoke exclusively to TheGayUK about the themes of the show, why provocative theatre remains relevant and how Freddie Mercury changed his life.

TGUK – You have chosen quite a provocative title for the piece

JG – Yes, and it was very deliberate for a number of reasons. It stems from a friend of mine who I met at a festival who texted the word to me during an argument. I was astounded that someone would not only use that word towards someone who was a friend to them, but that they had typed it; they had spelt it out letter by letter – F-A-double G-O-T – and just how hurtful a word it was. But then it’s also about seizing ownership of the word for the LGBT community; about taking possession and disempowering the word by taking it back. Queer was used as an insult historically, but in recent years it has been taken back by the LGBT community and turned into a positive label. I wanted a title to reflect one of the aims of the show, which is about confronting and challenging the audience to look at issues of prejudice, racism and homophobia.

TGUK – Why do you think pieces of theatre like this are still important?

JG – Things have changed a lot, but there is still a way to go before prejudice is eradicated. Theatre is an art which has the power to do many things, and it is not just about being entertained. Of course, I want audiences to be entertained when they come to the show, but also I want them to be challenged; to look into themselves and to look at their own experiences, regardless of where their experiences lie. For the LGBT community, I hope that they will see glimpses of themselves reflected in my experiences. For straight audiences, I would hope that they either see some of the experiences that members of the LGBT community have to go through, which they themselves may not have experienced first-hand; or for them to see the impact of prejudice upon the victim. I also want younger people who may be struggling with their sexuality to come to the show and see that they are not alone; that their feelings are not unique; that they are not isolated. There are a lot of us out there, and despite the confidence that some people exude, for the vast majority of gay men and women, there has been that fear, that self-loathing and ultimately that transition into acceptance of their sexuality.

TGUK – You owe a lot to Freddie Mercury, don’t you?

JG – Freddie was the catalyst for my self-acceptance; the flamboyance and confidence he exudes made me realise that I could be the person who I wanted to be. I think most people have “a Freddie” – whether it is a person in the public eye, a friend, a family member or even an experience or moment where everything seems to suddenly fall into place.

TGUK – You have a real mix of influences in your life, your mother is from the Caribbean, you were born in Boston, Massachusetts, and you moved to Leeds when you were 11. How did you find your voice with such a varied influence of cultures?

JG – My mother is a very traditional Caribbean woman; religious, larger than life, joyous and uplifting. My experiences in America helped to shape a lot of my perceptions about myself and those around me and being brought up in Leeds, I do have a lot of “Northern mentality”. I am, in many ways, still finding my voice, and I think that every day brings something new to shape you as a person and as an artist. I am fortunate to have so many different influences from my family, friends and those around me.

TGUK – How did you reconcile your religious upbringing with your sexuality?

JG – Religion told me I was a sinner, an abomination. I was told by people in my school that I was going to go to hell. I used to pray to God to pray the gay away. But as I grew older, I was able to balance myself and my religion. I believe in the concept of a god, but I am of the view that I can believe in God; but because my race is so important to me I find it hard to believe in the bible, primarily because of the history of colonialism and the use of the bible in that process. When I look at the link between colonialism and the Bible, it is not something that I want to embrace or accept. My black heritage and my identity as a black man is something that is more important to me than my sexuality is; and the way in which the bible was used during that period of time was wholly unacceptable. For me, it remains a symbol of repression in many ways. It was used to repress the black community many years ago and, in my experiences as a younger person, it was used to repress my sexuality – but despite that, it doesn’t prevent me from embracing the idea of a higher power.

TGUK – One of the themes of your show is about your experiences as a black gay man. How has your ethnicity and your sexuality shaped your experiences of life?

JG – I have received so much acceptance and positivity about both of those things that it is hard to express some of my experiences without sounding like a cynic. The positive experiences do outweigh the negative ones, but during the show, I talk about my experience at a sex party, where a guy I was with only wanted to sleep with me because I was black and made a mood spoiling comment (when we were in the moment) about my ethnicity; and I do a section in the show about my experiences on Grindr, where the fact that I was black was often the predominant issue. It’s the usual stereotypes and prejudices; I’d get messages saying “Is it true what they say about black men?” or “I’ve always wanted to be with a black guy”; it made me realise that they didn’t necessarily want to be with me as a person, but that being black was just fulfilling a fetish for these men. It brought home to me the way in which black men can be perceived at times by others, almost as a commodity rather than a person. Racial fetishism is a subject which is not often talked about and it is another wall I want to break down with the show.

TGUK – Have you experienced more racism or more homophobia?

JG – It’s difficult to say; there have been times in my life when things have gone through phases. When I was at school, it was more about homophobia, as I went to a school in Leeds which was quite diverse, so ethnicity was not a particular problem. But as I went into higher education; it became less about my sexuality and more about my race. I have experienced both at the same time – when I was at school, someone wrote “Go home to Jamaica, Batty Boi” on our dustbin . That hurt – a lot. Given that my family is from Montserrat, it was an attack on my heritage and on my sexuality. I am naturally quite a flamboyant person, but I can hide my sexuality; I can’t hide the colour of my skin, so I would guess that would perhaps identify my ethnicity as the most obvious target. That said, I still identify myself as a black man first and a gay man second. When you look at the news about what is happening in America at the moment, with the rising racial tensions both politically and on the streets; and you look at the terrible tragic events in Orlando only a few months ago, both racism and homophobia are very much alive and predominant in society.

TGUK – When you are on stage performing this piece, you lay yourself bare, both metaphorically and literally. How does it feel to relive highs and lows of your life night after night on stage?

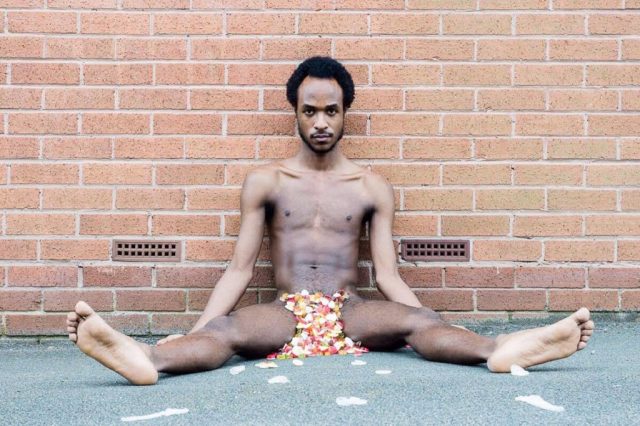

JG – It can be emotionally draining and it can be cathartic. Despite its simplistic presentation, it is quite a deep piece. I talk about things which are really difficult for me; such as my internalised homophobia as a younger man; the moment I came out, my experience in the church and about relationships which have hurt me in one way or another; but that is counteracted by the fact that I also talk about the positivity I have experienced. It’s not just about reliving the hard times; it is also about constantly remembering and reinforcing the positive steps on the journey which have led me to where I am today. By performing the majority of the piece in just a pair of short, black, tight trunks, it shows that I am hiding nothing, that I am open and honest. There is nothing to hide behind on the stage, not even clothes, and it is about reflecting that I am quite literally exposing my life, my thoughts, my experiences to the audience.

TGUK – You use a lot of symbolism to tell your story

JG – There is a section where I eat a raw onion in the show. On a simplistic interpretation, it may look like the usual analogy of an onion having layers and about how that is reflective of me as a person, which may look almost cliché. But it is deeper than that; the symbolism behind it is that, as anyone who sees the show will tell, I hate onion and consuming it is symbolic of ingesting something that I hated, of my repressed sexuality as a youngster and of my internalised hatred of who I was as a result of my cultural experiences growing up. The piece has a lot of aspects which have multiple meanings and it is for the audience to draw out their own conclusions about what the piece is saying. My show is, in some ways, a gift to the audience. They can take it and use it how they want. They can accept the gift and enjoy it, they can appreciate it, pass it on, re-gift it or put it in the cupboard – but it is something I offer to them with a genuine intention; what they then do with that is up to them.

TGUK – You end the show painting yourself in the colours of the rainbow flag. Why chose that piece of symbolism to round off the show?

JG – I wrote a poem some years ago where I used the line “ripping rainbows apart” and I wanted to bring that line to life. But also because the rainbow flag is a symbol reflecting both sexuality and colour, which is what this piece is about. It felt a natural way to bring the piece full circle. Ending the show embraced in the colours of the rainbow flag feels comfortable and is about how, despite their differences, the LGBT community do embrace each other. The flag gives us protection and a sense of togetherness. How else could I end the show except for showing the unity and the positivity of the LGBT community as a whole?

FADoubleGOT is currently on tour, calling at The Hive in Shrewsbury (30.09.16); Hackney Showroom in London (04.10.16), as part of the And What? Queer Arts Festival; Live Art Bistro in Leeds (14.10.16); Camden People’s Theatre in London (18.10.16 and 19.10.16) and Theatre Deli in Sheffield (17.11.16). You can follow Jamal on Twitter at @JamiBoii and on Tumblr at http://jamalgerald.tumblr.com/ . Many thanks to Doncaster CAST Theatre (www.castindoncaster.com) for facilitating this article.